West Virginia teachers won’t back down

Thousands of teachers stunned West Virginia politicians and employers by launching a strike on February 22 in a fight against a miserable pay increase and a freeze on scheduled improvements to health insurance benefits. But they had another surprise in store when the walkout continued into this week in every part of the state.

, a West Virginia high school teacher, sent SW this report about a strike that saw teachers from all 55 West Virginia counties take to the picket lines--with many converging on the state capital of Charleston for demonstrations.

WITH THE close of the second day of a statewide teachers strike last Friday, West Virginia Education Association (WVEA) President Dale Lee finished a long day at the state Capitol by declaring to the assembled media that the walkouts would continue into the following week.

Lee, American Federation of Teachers (AFT)-West Virginia President Christine Campbell, and thousands of other teachers and other public service employees flooded the state capital of Charleston the previous day, bringing traffic on the I-77 highway to a standstill.

"A strike signals to the state that we will not back down," said K., an elementary school teacher from Logan County.

As a striker myself, the impact of the walkouts signifies to me a mass people-powered movement, bringing together a coalition of various labor sectors to seek change by any means necessary.

A victory here would send a message to elites around the country that the labor movement--which had appeared effectively neutered with the rise of "right to work" laws and the impending anti-union Janus decision by the U.S. Supreme Court--will see a resurgence in this decade.

Furthermore, a victory would provide opportunities for future mass actions directed against the state, as demands for a people-centered destiny, centered around labor, become more concrete.

Outside the Capitol building on February 23, educators talked about waiting hours in long lines to enter security and voice their concerns to legislators.

"We'd rather be in the classroom," David Bannister, a physical education teacher, told the Metro News. "But we have to take care of our families, too. We have to get their attention. We haven't been able to get it any other way, so here we are."

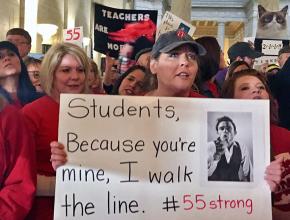

Once inside, the Capitol rotunda became a sea of red--the official color of teachers across the country--as chants of "We won't back down,""55 United" and "55 Strong" echoed through the building. The number 55 referred to the number of counties in West Virginia--union teachers are on the picket line in each and every one.

PRIOR TO the walkouts, the Republican-dominated legislature made an ultimatum to teachers to prevent a strike: a 17-month freeze on any alterations to the Public Employees Insurance Agency (PEIA) plans, which covers health care for most public employees and had been scheduled to increase over the next four years, and a 4 percent increase in teacher pay spread out over three years.

For context, a 1 percent increase in teacher pay would amount to a $404 increase annually.

Union leaders scoffed at this offer, and the walkouts on Thursday and Friday proceeded as planned.

Across the state, there were pickets set up to block roads and send a message. In many instances, local coffee shops, pizza places and everyday individuals dropped off food, water, coffee and hot chocolate to keep up spirits and feed those on strike. This sense of solidarity permeated most counties, as recognition of a common purpose abounded.

When Lee called for the statewide walkout to continue February 26, union representatives were taken aback. Counties had held informational gatherings earlier in the week in preparation for a rolling walkout until the legislative session ended on March 10.

The theory was that a rolling walkout would counteract upcoming injunctions against union leaders for each county where a walkout continued. Thus, five counties would be chosen at random to walk out on a given day, show up to the Capitol or picket their school, and physically shut down schools in that county.

The tactic would ensure that county superintendents would know which county would call a walkout that day--so it would take up significant time for officials to file injunctions. By the time the legal actions were filed, teachers would be back in the classrooms, while another set of five counties would go out.

In a private Facebook group for West Virginia public employees, posters complained that a rolling walkout would not help. "I went on strike in 1990, and we won because we all went out at the same time, and stayed on the line," one poster wrote.

It appears that Lee's decision to continue the walkouts the following week was a reflection of the anger against the rolling walkout plan. Independent sources stated that county superintendents had been prepared for school to begin again on Monday, and when they learned that the statewide strikes would continue, they were taken by surprise.

MANY EDUCATORS--and, indeed, the country at large--are watching and waiting, wondering what will happen next.

One possibility is that the teachers' unions seek compromise. Union leaders are bargaining for a 5 percent raise over the next five years, amounting to almost $10,000 in raises over the next half decade.

Alongside this, they demand the permanent tabling of any bills that would eliminate teacher seniority in transfers and firing, or create or implement charter schools. They also want a permanent funding source for all PEIA-related concerns.

The likelihood that a legislature and governor's mansion controlled by the Republicans will agree to this is slim. More concerning is the fact that West Virginia's U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin, a Democrat, arrived in the capital this weekend for a photo op and to meet with union leaders.

Manchin's arrival should be feared by those who seek to use this strike to alter the socio-economic destiny of the state. The senator is up for re-election this year and faces an uphill primary against a progressive single mother, Paula Jean Swearengin, along with a host of potential Republican challengers.

This appearance could signal that the national Democratic Party wants to ensure that Manchin appears strong and capable of negotiating state-level concerns. Any compromise reached as a result of his involvement would signal the end of the statewide strike, even if union leaders ask members to provide them with feedback on the decision.

Another possibility is that Republicans could stall and drag out a special session of the state legislature. In this scenario, there is no particular end in sight for the strike, but simply a series of negotiated walkouts in counties or across the state until the end of the state's regular session.

Republicans in the legislature realize that they might be able to wait out a strike until March 10--in which case, they could theoretically attempt a compromise with a beleaguered state and communities that would, by then, demand any change, so long as children could return to school.

Moreover, legislator pay for a special session is more than $500 per day, something that Republicans could tout as damaging to the state's budget, blaming educators for the mess, though conveniently leaving out their stalling over the course of the month.

IT'S ALSO possible that grassroots efforts force union leaders to continue the strike indefinitely. The initiative that began with a private Facebook group--and forced union leadership to act initially--could pressure officials to continue statewide action until demands are met.

Both the AFT and WVEA will hold their statewide meetings in April. So there is a real possibility that leadership will fear a backlash by members should union officials compromise too early or without something substantive as a victory.

After all, WVEA President Lee initially took control of the statewide talk of a strike once he found out that grassroots efforts on the private Facebook group had garnered too much attention for him to halt back in October 2017.

Under this scenario, however, a compromise will be more favorable to unions financially, but will do little to alter the balance of the political and economic destiny of the state.

There is also the possibility of a crackdown by the state--one that could lead to a mass political shift.

Jake Jarvis, a reporter for the Charleston Gazette-Mail, reported February 23 that the House of Delegates voted to give Capitol police authority to break up "riots and unlawful assemblages," and would prevent them from being held liable "for the death of persons in riots and unlawful assemblages."

Posters on the Facebook group were quick to point out that this was an update of a 1933 law that was long in the works for legal reasons. But others pointed out the coincidence of the timing--when upwards of 5,000 educators poured into the capital to demand change.

We shouldn't discount the possibility that police would resort to mass arrests and potential violence against educators to do the bidding of reactionary legislators. During recent health care sit-ins, for example, an Episcopalian priest was led off in handcuffs.

It is not too far off to imagine a situation where the legislature pits one public sector against the other, and then argues they had done so under the guise of law and order. While bleak, this scenario may open up possibilities for future left-wing union and political organizing as a direct result of state pressure forcing workers to take sides, rather than simply returning to electoral strategies.

IN ANY case, West Virginia is seeing the blossoming of a mass political movement that has no clear trajectory or end in sight--and perhaps that is ultimately a good thing. It prevents those in power from preparing a thought-out plan to prevent the mass of public employees from coming together for change, while simultaneously allowing for flexibility among workers to determine how to respond in each new situation.

The working-class struggle in the Mountain State goes back more than a century. This newest iteration is in part a response to the decades of neoliberal capitalism and its inability to provide adequate funding for social services or worker autonomy.

The teachers' strike is making inroads nationwide because, at its core, it is a challenge to the unjust economic and political nature of our society.

As a West Virginia public school teacher, I can only hope that this movement sparks something larger than us, transforming the whole of society in the process. The eyes of the nation are watching.