1968: The year that changed everything

Socialist Worker begins a yearlong series marking the 50th anniversary of 1968 with an article by on how the stage was set for a revolutionary year.

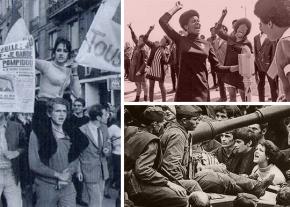

THE TET Offensive in Vietnam. The assassination of Martin Luther King. The French May. The Prague Spring. Black Power fists at the Olympics in Mexico City. Mayhem outside the Democratic convention in Chicago. Marching for civil rights in Northern Ireland.

To name the year 1968 is to summon images of not just one or two world-shaking events, but many.

If you aren't familiar with everything on this list from 50 years ago, it's not your fault--we aren't taught the history of resistance to oppression and tyranny. So it's the job of the left today to remember the revolutionary year of 1968 and the lessons it holds.

And there are many: even the strongest-seeming regimes can be shaken by uprisings from below; political change is infectious and can take place at lightning speed; the spirit of freedom can sweep across the world, from the poorest and most subjugated countries to the richest and most powerful.

Mainstream accounts of 1968 are different. They typically tell about only some of the participants--to peddle a caricature of pampered students acting out, on the basis of naïve ideals they didn't really understand and later abandoned.

It's a false picture in so many ways, but the smear lives on. Many people reading this article may have had their efforts at political activism dismissed as a "throwback to the '60s." There's an irony here: The small core of radicals around at the beginning of the major struggles of the 1960s were often accused of wanting to "relive the 1930s."

Contrary to the efforts to erase their legacy, the struggles that came to a head or reached a turning point in 1968 were a profound challenge to a society of rulers and ruled. They stopped a war and changed the balance of imperial power; they shook whole governments and political systems to the core; they tore away the thin tissue of propaganda that served to justify authoritarianism, East and West.

It took an immense effort by ruling classes around the world to withstand the surging tide that crested in 1968 and reverse it with a conscious and coordinated conservative backlash that has lasted throughout the decades since in many countries.

But even after the years of neoliberalism and repression that followed, our society would be unrecognizable without the achievements that endure from the high points of the 1960s and early '70s social movements.

Socialist Worker contributors remember the great struggles of the revolutionary year of 1968 — and the lessons they hold for today.

1968: A Revolutionary Year

1968: The year that changed everything

1968: Tet and the watershed in Vietnam

1968: When King’s murder set off the uprisings

1968: Revolution reaches the heart of Europe

1968: A revolt blooms behind the “Iron Curtain”

1968: SDS and the revolt of the campuses

1968: The rise of the Red Power movement

1968: A war on dissent in the streets of Chicago

1968: Women’s liberation takes the stage

1968: The massacre in Tlatelolco

1968: The Nixon backlash and the “silent majority”

1968: The strike at San Francisco State

In the U.S., they doomed the system of Jim Crow apartheid in the South and challenged racism and poverty in Northern cities, leading to a vast expansion of state-sponsored programs and initiatives that benefited all working people. Opportunities in employment and education were opened up, and the ideological transformations accomplished by the women's liberation and LGBT liberation movements shape our society today, despite the conservative backlash.

With its 50th anniversary taking place in the foul era of Trump, it's all the more important to take inspiration from 1968's examples of the mighty brought down--and of ordinary people changing the world.

THE NEW generation of revolutionaries that came of age in 1968 grew up in an era that was anything but revolutionary.

The 1950s was an era of political reaction and stultifying conformism. Consider 1968 in the light of these results from a survey done a decade before: Among young male college students, 40 percent could think of no way--not one--that they wanted to be different from their fathers, while 46 out of 50 sophomore women said they expected that they would graduate, get married to a professional or junior executive, and raise a family in the suburbs.

The basis for this conservative era was a long period of relatively stable economic expansion that followed the Second World War. Living standards for working people grew as never before or since.

This was the "American Dream," and while some sections of the population, especially African Americans, were excluded, it seemed to spell the end of the bitter class conflicts that defined the Great Depression era that came before.

In most countries, the ideology and policies of center-left or labor-based political parties converged with the center-right. Within the U.S. labor movement, as elsewhere, it was accepted that workers' interests aligned with corporations in creating a more prosperous society for all.

Even among those on the left repelled by the inequalities and oppression caused by capitalism, it was commonly accepted that class struggle was a thing of the past. Herbert Marcuse's influential One Dimensional Man was typical:

Technical progress, extended to a whole system of domination and coordination, creates forms of life (and power) which appear to reconcile forces opposing the system....The "people," previously the ferment of social change, have "moved up" to become the ferment of social cohesion.

Meanwhile, international politics were dominated by the Cold War between the U.S. and the former USSR. Aside from a very small number of revolutionary socialists, all parts of the political spectrum aligned themselves with either Washington or Moscow.

This contributed to the political conservatism of the era. Faced with protest or even just criticism, the ideologists of the West could point to the tyranny of the Stalinist system in the USSR and the East as the inevitable outcome of any attempt to change society--while the ruling elites of the East justified a system that crushed political dissent as a necessity against the enemies of the West.

But there were other dynamics at work beneath the seemingly calm surface of 1950s and early '60s society.

For one thing, expanding living standards for the working class raised expectations of a better life for a generation raised during the Great Depression.

Plus, there were the contradictions of a political system that preached democracy and freedom, but practiced authoritarianism at the least provocation. America was the "greatest democracy in the world"--unless you were or ever had been drawn to the ideals of socialism, or happened to be Black and living in the Jim Crow South.

In countries around the world, in both similar and dissimilar ways, different groups of people--perhaps small at first, but with the potential to grow--found ways to dissent from the status quo, laying the basis for resistance.

THE IRREPRESSIBLE revulsion against injustice gave rise to the social struggle that shaped all others in the U.S.--and, in many ways, around the globe: the civil rights movement in the Jim Crow South.

The struggle had been building for years. The experience of African American soldiers during the Second World War--fighting a war for democracy, and then returning home to Jim Crow segregation--was especially important.

Growing pressure domestically--and internationally, as attempts to present the U.S. as the guardian of freedom were embarrassed by the continuation of an apartheid system in the South--began to produce change from above, exemplified by the U.S. Supreme Court's 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision outlawing segregation in public schools.

But it would take more than court decisions to make desegregation reality. As of 1960, only 17 Southern school districts were desegregated by the standards of the Brown decision.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-57 was an inspiring illustration of the determination of Southern Blacks to challenge Jim Crow, but the era of mass direct action really got going with the second phase of the movement in 1960.

On February 1, four students from the historically Black North Carolina A&T sat down at the whites-only Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro and asked to be served a cup of coffee. They were refused service--and they refused to leave until the store closed.

It was the pebble that started an avalanche. The next day, 23 students sat in. On the third day, there were 63--and on the fourth, more than 300. Within two weeks, there were lunch-counter sit-ins in 15 Southern cities--and more than 100 cities before the year was out. By then, tens of thousand of young African American men and women had taken direct action against Jim Crow.

With the protests came new political networks and formations. Sit-in organizers came together in April to form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

This is a pattern repeated in every radical moment: Those energized by the cause seek to consolidate themselves, using old political organization if it serves the purpose--and creating new ones if the old ones stand in the way.

The struggles of the coming years would set an example followed around the U.S. and the world in the coming years.

In 1963, more than 200,000 people attended the March on Washington where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his "I Have a Dream" speech. The next year, SNCC carried out its boldest initiative: the Mississippi Summer Project, which made use of solidarity among Northern white college students to bring volunteers to Mississippi to defy Jim Crow.

All the while, a new generation was getting a rapid education in political realities. When a civil rights delegation was betrayed at the 1964 Democratic Party national convention--betrayed by liberals who mouthed support for civil rights in the South, but didn't tolerate any threat to their own power--it was the final straw for many who had expressed quite moderate politics only a few years before.

"Never again would we be lulled into believing that our task was exposing injustices so that the 'good' people of America would eliminate them," said SNCC leader Cleveland Sellers.

With that conclusion, new debates and discussions about how to change society set the stage for the further radicalization of the movement--and the emergence of organizations like the Black Panthers that would play an important role in 1968.

THE CIVIL rights movement trained a core of activists, Black and white, who would put their experiences to use in the new student movement on university campuses.

College had not been a primary arena for radical politics in the past because of its exclusivity. But the needs of capitalism in the post-Second World War era changed the universities from primarily a preserve for the training of the ruling class to a much broader social institution.

This also transformed the role of students in society. No longer destined to rule--though a significant minority would--many students came to question a system that claimed to value knowledge and individual expression, but seemed organized to churn out carbon-copy conformists to serve the needs of the system.

The first activities of a new campus left were often taken in solidarity with the civil rights struggle, and later against the Vietnam War. But these connected with a deeper sense of alienation and discontent--something Mario Savio, a leader of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement, gave expression to in a 1964 speech:

There's a time when the operations of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can't take part; you can't even passively take part. And you've got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you've got to indicate to the people who own it that unless you're free, the machines will be prevented from working at all.

Savio crystallized a sentiment that existed in the newly expanding university systems of countries around the world. But as the 1960s continued, it was opposition to the expanding U.S. war on Vietnam that galvanized the student radicalization--especially in the U.S., but also in other countries.

The U.S. intervention began in earnest under Democratic Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Washington's aim was to stop a national liberation struggle from toppling a reactionary regime and bringing Vietnam into the orbit of the Eastern bloc.

But as U.S. involvement escalated, masses of ordinary people learned the obscene truth, usually hidden from them, about their empire's alliances with dictators and willingness to use the world's most deadly arsenal.

Like the civil rights movement, the antiwar struggle began modestly. For example, some of the most successful early actions utilized a tactic that was specifically opposed to protest and direct action--campus teach-ins that allowed pro-war voices to make their case.

But by defeating the polished representatives of U.S. imperialism in public debate, antiwar organizers won more and more people to their side. Within a couple years, protests that had drawn hundreds and thousands now brought out tens and hundreds of thousands.

Critiques of the war spread. But it would take the first political earthquake of 1968--the Tet Offensive, launched on January 30 by the forces committed to North Vietnam's national liberation against the U.S.-backed South Vietnam government--to turn the tide of establishment opinion and boost the antiwar struggle into a truly massive movement.

THE ARTICLES in SW's series will take up the conflicts, struggles and movements of 1968 in greater detail. But throughout that year that changed everything, there's an underlying theme: the electrifying experience of struggle and how it changed a generation.

The most important legacy of 1968 is what the world looks like when masses of ordinary people take action to change it.

That inevitably involves a period of politicization that can only be resolved with political debate and discussion. As the American socialist Hal Draper, a prominent figure in the early 1960s struggles, explains:

The initial motive power of all radical movements has always been the elemental revulsion of people against the felt evils of the status quo, whether a revulsion powered by interest (the legitimate interest of people who feel those evils on their own backs) or a moral revulsion by individuals who are not themselves oppressed but who identify with the oppressed...

This is how a social movement starts, and this is what remains the source of its motive power. But every social movement worth its steam has next had to do something more--or else peter out.

If the "elemental revulsion" of one kind or another is the locomotive, then the people on the train have got to acquire a few more notions before the locomotive can go anywhere. There are the problems of routing, and braking at the proper times; there are track forks; sometimes even new track may have to be laid in a chosen direction; it becomes necessary to have a sketch map of the territory; relations with other locomotives (known as time tables) have to be taken account of...

The point is that the locomotive is a necessary but not sufficient equipment for railroading; and moral fervor is a necessary but not sufficient basis for revolutionary politics.

On a mass scale, the radical and revolutionary conclusions drawn by millions may not have survived the defeats of the years to come. But for every turncoat who grabs headlines by sneering at the 1960s, there are many more who remember a profoundly important time. As one volunteer during the Freedom Summer project of the civil rights movement remembered:

The memories of that summer are very important to me because they...[serve] as a reminder to me that there are qualities in me that are worth something and that people are capable of quite remarkable things. It's the single most enduring moment of my life. I believe in it beyond anything.