How Local 804 said no to Hoffa’s sellout deal

reports on how Teamsters Local 804 in New York City took a stand against a concessionary contract at UPS, in an article first published at Jacobin.

AFTER MONTHS of contract negotiations between UPS and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, the union’s chief negotiator announced that the union had reached a preliminary agreement. But as soon as the details of the contract were released, Hoffa and his negotiating team faced scrutiny: the reform caucus Teamsters United (TU) and the longstanding union reform organization Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) were not happy.

TDU argued that workers wanted stronger wage increases, more full-time jobs, clear language around managerial harassment, and an end to forced overtime that currently has many employees working up to 70 hours a week during peak season, the period between November and January when UPS experiences the highest shipping volume. Instead, the proposed agreement included a new two-tier wage system for drivers, effectively paying one classification of workers less to perform the same job tasks as their full-time counterparts. The agreement also included a starting wage that falls $2 short of the union’s proposed $15 per hour rate, no clear penalties for managers harassing workers on the job, and language that makes it harder for new workers to join “the 9.5 list,” a classification which protects them from being forced to accept overtime.

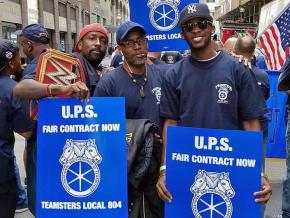

Once the contract details were released, a number of union locals began using TDU and TU materials to form “vote no” contract campaigns that were aimed at keeping the preliminary contract agreement from being ratified. Nowhere was this campaign more successful than Local 804 in New York, where 95 percent of workers voted down the contract. This vote of no confidence was achieved by rank-and-file UPS workers convincing their coworkers that this contract did not deliver the goods.

Prior to the vote results, Local 804’s leadership had largely remained quiet about the preliminary agreement. The success achieved by the “vote no” campaign resulted in the contract committee refusing to accept any of UPS’s proposed concessions during a three-day-long negotiation session over their contract supplement, which covers regional contract issues and additional provisions around pay and benefits. Negotiations over the supplement are still ongoing. But this show of force is a significant step forward for the workers, whose aim is to win better wages and working conditions for the entire membership by rejecting what they consider a concessionary contract.

UPS IS the largest unionized private-sector employer in the U.S.; its contract will cover over a quarter of a million workers. For the past few years, it has seen massive growth and record profits. As volume continues to rise, employees are working at a faster pace and for longer hours than ever before.

The June strike vote was a show of force, with members voting 93 percent to 7 percent in favor of authorizing a strike. Yet the union leadership, headed by James Hoffa Jr., was not only reticent to push the company to deliver a strong contract, but willingly offered them concessions, suggesting the addition of a new, lower-paid classification of drivers, known as “hybrid drivers,” as a solution to relieving the amount of overtime that UPS workers are forced to incur. Rather than use the strike vote as leverage to extract concessions from the company, Hoffa actually came up with new concessions to offer the company himself.

One such proposal is for hybrid drivers, also known as “22.4s” (named for the section of the contract where the classification would appear). This job classification combines a variety of part-time jobs for the company into one 40-hour position. The flexibility of the classification allows the company to assign these workers to jobs as needed. The downside for the employees is that they would be working a variety of low- and higher-paying jobs for the company, bringing their pay scale down below what the full-time package car drivers make — even if they are doing the same work.

Hybrid drivers will work either Tuesday through Saturday or Sunday through Thursday. This allows UPS to expand out a Sunday delivery service without having to pay their full-time drivers overtime for weekend work.

Once it became clear that Hoffa was pushing such a concessionary contract, UPS workers around the country began building a “vote no” campaign. A package-car driver from Wisconsin named Tyler Binder became something of an internet sensation by creating a YouTube video that walked members through “Why the UPS 2018 contract sucks.” The video aimed to unite the union membership against the contract down in order to force the union leadership and the company back to the bargaining table.

Three days before the deadline, news broke that Amazon would implement a $15 minimum wage including catch-up raises for existing part-time workers starting November 1, meaning that existing Amazon workers would receive additional pay bumps based on how long they had worked for the company. Many Teamsters were incensed: under their proposed agreement, part-time unionized drivers would earn $2 less in starting pay than their nonunionized counterparts at Amazon. The pay gap widens even further for part-time UPS workers with a few years on the job, who were not offered catch-up raises and will also be making $13 an hour under the new contract.

Union leaders all but giving away the farm is an all-too-frequent occurrence in contract negotiations, but Hoffa’s lead negotiator Denis Taylor took things a step further at a national grievance panel two days before the end of voting. He reminded members that the union could still implement the contract if less than half of the membership voted and less than two-thirds of those voting voted it down.

Even though this rule has been on the books for decades, Taylor’s threat came as a surprise. As TDU points out, “No national contract has ever been ratified after a majority of members Voted No since the revised two-thirds rule went into effect in 1987.”

Both of these developments spurred one last “vote no” push by the rank and file, TU, and TDU. By the evening of October 5, the tally was in. A little under half of the membership voted; the “no” vote was 54 percent — a clear majority, but the total number of votes fell short of the two-thirds rule.

Despite the union using this rule to ratify the national master agreement, the contract cannot be put into effect until all of the local supplements are ratified. The master agreement provides overarching basic provisions for all of the locals covered by the contract, but the supplements cover both the issues specific to work in each geographic region and in some cases include language around increased pension contributions, managerial harassment, paid sick days, and more that go beyond what is laid out in the national contract.

After the vote on October 5, the question became which locals were able to vote the contract down, and would these locals mobilize against Hoffa if he tried to implement the national contract over the objections of a majority of voting UPS members?

In the end, ten of the local and regional supplements were voted down, but only five were voted down by a high enough margin to meet the quorum rule. The local with the highest “no” percentage was 804, with 95.34 percent.

This is not the first time that Local 804 has been at the forefront of a struggle inside the Teamsters. For decades, it was at the center of national reform efforts aimed at winning power away from union leaders with ties to the mafia and restoring democratic power to the membership.

RON CAREY started as a package-car driver in Local 804 and became president of the local in 1967. He later became the reform candidate for union president, backed by groups like TDU, in the wake of a federally mandated process of democratization in the union. He won the presidency in 1991, then led 185,000 UPS workers out on strike in 1997. Soon after the strike, however, the old guard clawed its way back, and Carey was pushed out of the union on charges of corruption. All the charges were later thrown out, but they served their purpose for the old guard: Carey was banned from the union for life, and James Hoffa Jr took over as the national president of the Teamsters.

The 1997 UPS strike was one of the largest and most successful national strike victories since the 1970s. It won widespread public support, created thousands of full-time jobs, safeguarded pensions at a time when pension plans at private companies were largely being dissolved, and won a strike at a time when unions everywhere were losing. But since the strike, the union has largely waged a defensive battle.

Currently, 804 is in the middle of electing a new local leadership. The legacy of Ron Carey and the ‘97 strike are informing the character of this election. The Experience Matters slate describes itself in opposition to the “Executive Board [that] has been in Hoffa’s pocket.” (One of the slate’s candidates even talks about attending contract negotiations under “the great Ron Carey.”) Their focus on de-seating Danny Montalvo and the other members of the “Members First” slate is being framed as a way to take back the union for the membership in very similar language used by Carey himself when he vowed to bring the power of the union back into the hands of the workers.

Even after decades of concessionary bargaining and a national leadership that has been accused of not acting in the interests of the workers, Local 804 has retained a network of workers that want to fight for a better contract for the entire membership. It is largely these drivers and the stewards that led the “vote no” campaign to victory in 804.

MANY OF the workers leading this fight started for UPS when the union went out on strike in 1997. Today, that informs many workers’ approach to the contract — fighting the company rather than keeping up friendly bargaining relations with them.

Anthony Rosario is such a driver. He started working two-part time jobs at UPS in 1994 when he was nineteen. In a recent interview for Socialist Worker, Anthony described why he went out in 1997 and how he feels that the company is trying to force many of the same concessions back on UPS workers today:

I started in 1994. Guys like me were working two different part-time shifts and not getting full-time pay .... This strike was a big deal for me because ... I was finally able to start working full-time as a UPS driver and making some decent money. I was one of the guys who was able to slip in after that time period. From what I see from these negotiations now, they are basically trying to get these guys to work at a lower pay.

Anthony and his chief shop steward Juan Acosta have been at the center of building the “no” vote at Local 804’s Foster Avenue hub in Brooklyn. During this campaign, UPS workers used Facebook to organize against the contract, much like the teachers who led a wave of strikes for public education this past spring. Local 804 members created “vote no” contract negotiation groups and posted articles on the various Teamster pages criticizing the national union leadership for posting fake “vote yes” testimonials. In the hubs, drivers described managers talking to new part-time workers about why the contract was strong and instructing them to stay away from older drivers. In Local 804, these attempts failed to produce “yes” votes.

Faced with a strict dress code that doesn’t allow for the common tactic of workers wearing a certain color on a particular day to show solidarity, members began wearing yellow “Teamster Contract Unity” bracelets. UPS workers also placed “vote no” placards in their personal vehicles and regularly left “vote no” fliers on their coworkers’ cars. Workers organized one-on-one conversations with their coworkers before and after work and on days off. They educated a new layer of new and part-time workers about the contract.

This led to larger actions. Every year, UPS celebrates “Founders Day,” marking the day the company was founded on August 28, 1907. This year the Foster Avenue hub workers celebrated by holding a “vote no” rally that drew around 150 employees. Since then, members have continued to hold meetings in the ones and twos, meeting off the clock to try to unite full- and part-time workers, drivers, and loaders against the contract.

Some stewards like Juan Acosta have even used their vacation time to talk to workers from other states about why they should reject the contract. During a recent interview, he said, “I’m proud of my local. I’m proud of the guys and girls that went out to spread the no vote. I did my part. I went to Colorado and talked to the guys out there.”

Currently petitions are circulating both locally and nationally calling on Hoffa to recognize the “no” vote and not to push forward with ratification. But it seems likely that it will take more to push the union leadership back to the negotiating table. As peak season looms at UPS, the Teamsters have a major advantage. If they were to call a strike during the busiest time of year, it would cost the company millions of dollars.

At this stage, it’s hard to say what will happen if Hoffa tries to implement the national contract at UPS. Local 705 in Chicago, which has a separate contract from the national agreement, is still in negotiations. Perhaps other locals will lead more rallies, or sick outs like teachers in West Virginia. Maybe strikes will spread from local to local. Whatever actions workers decide to take, it will likely come from the locals who organized large “vote no” turnouts.

Prior to the “vote no” campaign, the local leadership of 804 was largely silent on the contract. The 95.34 percent “no” vote shifted the tides and forced the leadership to take a more confrontational stance. As Local 804’s website now states, “When UPS’s lead negotiator said that they were disheartened by the committee’s refusal to give the company what they wanted, Local 804 President Danny Montalvo shot back, ‘We have gotten nothing from you, and we are not going to back down!’” It will take more of this kind of pressure to make UPS and the union’s national leadership budge. Local 804 shows that it is possible.

First published at Jacobin.