Socialism on the campaign trail

examines the inspiring example of Socialist Party leader Eugene Debs for lessons about how revolutionaries view and participate in elections.

“We should seek only to register the actual vote of socialism, no more and no less. In our propaganda we should state our principles clearly, speak the truth fearlessly, seeking neither to flatter nor to offend, but only to convince those who should be with us and win them to our cause through an intelligent understanding of its mission.”

Eugene Debs, 1911

THE GROWING popularity of socialism is finding expression in down-ballot election campaigns this year, some led by candidates affiliated with the Democratic Socialists of America like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

The 28-year-old socialist stunned the Democratic Party establishment by winning the party primary election for a U.S. House seat in the Bronx and Queens, defeating one of the most powerful leaders of the Democrats in Congress.

In a political system dominated by two main parties that are so tied to upholding the virtues of capitalism, it’s rare to hear the word “socialism” used positively in a discussion of midterm elections. Plus, it’s refreshing to see the political establishment scramble to deal with candidates making popular pro-worker demands.

There is a long history of socialists participating in elections and a debate among different views about what the left’s goals and methods should be.

At the most basic level, elections are not irrelevant to socialists, even if we have no direct participation in them because there is no socialist alternative to support. They can gauge workers’ sentiments on various issues or signify shifts in consciousness to the left or right.

If socialists are able to initiate campaigns or contribute to those initiated by other forces, elections can be a further tool for presenting our politics to a wider audience and challenging the status quo. They can champion struggles and movements and the demands that emerge from them.

Beyond this, things have diverged historically.

The tradition of “reformism” has a long history of socialists putting a priority on using elections to attain political office, where they can try to legislate or administer their proposals, both modest and far-reaching, extending to the transformation of society, according to this view.

Some of these socialists and their parties have, with the support of working class struggle, achieved notable advances such as national health care, free education and union rights — though these reforms have been vulnerable to being taken away when ruling class parties regain the initiative.

The tradition of revolutionary socialism starts from the premise that socialism can only be achieved by the self-emancipation of the working class, not by electing political leaders into the capitalist state, where they can legislate socialism into being.

Elections are still an arena of political struggle for revolutionaries, but we assess the value of electoral strategies by whether they bring us closer to this goal by empowering the working class.

Winning office is not the goal. Even when revolutionary socialists have won elections, they understand that they will not be able to enact socialism on behalf of workers, so they regard holding office as an extension of the opportunity to present socialist politics and to champion the causes of workers, while exposing the injustices of the system.

This means we ask a number of questions about elections and socialist campaigns.

Is a campaign using its platform to not only raise popular working-class demands, but take a stand on more complicated issues of oppression and imperialism? Are socialists using any openings to direct anger at inequality and injustice in society toward opposition to the fundamental ways society is organized?

And in the U.S., where two capitalist parties, the Democrats and Republicans, take turns ruling in the interest not just of their corporate backers, but American capitalism itself, one big question is whether the campaign challenges the two-party system’s stranglehold on U.S. politics.

The narrow set of “choices” available to people in the U.S. in elections is propped up by the image of the Democratic Party as the “party of the people” — representing women, union members, Blacks, Latinos, etc., and at least slightly better than the Republicans on most issues.

But the Democrats’ number one priority is always maintaining its own power and serving the interests of some of “the people”: the rulers of the business and political world who ultimately control it. The party leadership and apparatus use the Democrats’ liberal image — and all the people who are attracted to work and vote for them because of that — to protect those priorities.

For these reasons, socialists in the tradition of Socialist Worker and its publisher, the International Socialist Organization, put a high priority on challenging the Democratic Party’s hold over the working-class movement.

WHAT DOES a socialist election campaign organized around these priorities and goals look like?

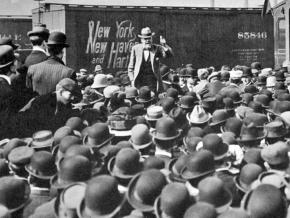

The presidential campaigns of U.S. socialist Eugene Debs in the early part of the last century provide some inspiring examples.

Through his five campaigns in 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912 and 1920, Debs used the electoral platform to spread the ideas of socialism, build the organizational strength of the Socialist Party, and take aim at capitalism and the parties that serve its interests.

This meant that Debs didn’t just talk about bread-and-butter issues and how, if elected, he might pass such and such legislation for workers. His campaign speeches were about how and why workers were exploited under capitalism, and why they were the ones who had the power to change this unequal state of affairs.

Debs’ attitudes were shaped by the fact that before he became a socialist, he had been an active member of the Democratic Party.

He was elected to the House of Representatives in his home state of Indiana in 1885. He learned through his own experience about the limits of holding office when a bill he supported to protect railway workers injured on the job was gutted by fellow lawmakers — and another supporting the women’s suffrage failed. After this, Debs vowed never to run for office again.

His experience as a leader of the American Railway Union — particularly during the 1894 Pullman Strike, when Democratic President Grover Cleveland called in federal troops and provoked violence, resulting in the deaths of 13 strikers — cemented his opposition to the Democrats and his commitment to socialism.

During his campaigns, Debs used his platform to explain why workers had to have their own organization independent of both capitalist parties. He suggested that disaffected Democrats should find a new place with the socialists, as he did in a 1904 speech in Indianapolis:

In referring to the Democratic Party in this discussion, we may save time by simply saying that since it was born again at the St. Louis convention, it is near enough like its Republican ally to pass for a twin brother. The former party of the “common people” is no longer under the boycott of the plutocracy, since it has adopted the Wall Street label and renounced its middle class heresies.

The radical and progressive elements of the former Democracy have been evicted and must seek other quarters. They were an unmitigated nuisance in the conservative counsels of the old party. They were for the “common people,” and the trusts have no use for such a party.

Where but to the Socialist Party can these progressive people turn? They are no one without a party, and the only genuine Democratic Party in the field is the Socialist Party, and every true Democrat should thank Wall Street for driving him out of a party that is democratic in name only, and into one that is democratic in fact.

During his 1908 campaign — with Debs traveling across the country on a train called the “Red Special” to campaign — he spoke to nearly half a million people.

Some 323 newspapers and periodicals took up the cause of socialism that year. The Appeal to Reason, one of the most widely read socialist papers, reached a circulation of 600,000 papers in 1912. Debs’ campaign translated not only into votes for socialism, but a significant growth in the membership of the party, especially in places where left-wing chapters supported local struggles.

As historian Ira Kipnis points out in The American Socialist Movement, 1897-1912, the SP in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, where members participated in union activity and strikes, experienced a 300 percent increase in Socialist votes from 1908.

WITHIN THE Socialist Party — which was a broad tent, including revolutionaries like Debs and more conservative socialists like Victor Berger of the Wisconsin SP — there were divisions about what could accomplished with these election campaign.

While Debs ran on a platform of workers organizing themselves and joining socialist organization, other prominent SP members disagreed with Debs’ revolutionary rhetoric and confined themselves to what they considered reasonable demands — with the idea that this would get them elected more easily, which was their primary goal as socialist candidates.

By 1912, infighting among the different wings with conflicting goals created disarray inside the party. Debs made an appeal at the time for the party to reject opportunism — including candidates tailoring their message to get elected — and affirm its commitment to socialist organization and the idea of workers’ power, with elections serving as only one means to these ends.

Debs made this plea in 1911 in an article titled “Danger Ahead”:

Voting for socialism is not socialism any more than a menu is a meal. Socialism must be organized drilled, equipped and the place to begin is in the industries where the workers are employed...Without such economic organization and the economic power with which it is clothed, and without the industrial co-operative training, discipline and efficiency which are its corollaries, the fruit of any political victories the workers may achieve will turn to ashes on their lips.

Obviously, much has changed since Debs ran for president 100 years ago, but his example can help guide socialists today.

If elections can help socialists convince others to be part of building an independent political alternative and strengthen left-wing organization at the grassroots, we want to participate — but this must include challenging the two capitalist parties that dominate the U.S. political system.