The ISO and the soul of international socialism

Forty years ago this month, the first issue of Socialist Worker appeared in the U.S., a few weeks after the founding of its publisher, the International Socialist Organization (ISO), on March 12, 1977. SW will feature an extended series on the history of the ISO over the coming months. For this installment, and trace the ISO's principles back to their roots in the Marxist tradition to provide a backdrop to the group's founding.

FORTY YEARS ago, on March 12, 1977, the International Socialist Organization (ISO) was founded at a meeting held in Detroit.

The first members of the ISO were shaped by the revolutionary times they had been living through.

Less than a decade had passed since 1968--the high point of a whole radical era. The year itself is still synonymous with revolution, having witnessed the French student rebellion and general strike, the uprising in Czechoslovakia, the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, and the tumultuous antiwar protests at the Democratic convention in Chicago, among other events.

In the course of these and other struggles, a new generation had rediscovered the emancipatory vision of socialism and the Marxist tradition in large numbers, though there were different and conflicting ideas about what these meant.

The commitment of this "New Left" was hardened by revolutionary struggles in 1968 and after--some of which put the question of socialism on the agenda: in Chile, with the election of a socialist government on the back of mass workers' struggles; in Portugal, where a dictator was overthrown in a revolutionary upsurge; in Iran a few years later, when mass strikes brought down the U.S.-backed Shah.

These world-shaking events were fresh in the minds of those who founded the ISO. But by 1977, the struggles of the working class and the social movements, at least in the U.S., were falling back from their heights.

Though it wasn't necessarily clear that this wasn't just a lull before the next upsurge, the radical ferment that had shaken the union movement in the U.S. was being pummeled by an aggressive employers' offensive, and the hard-won gains of the civil rights, Black Power, women's and other movements were under attack.

Nevertheless, the first meeting of the ISO launched an organization dedicated to achieving socialism, which is only possible through the kind of mass mobilization of the working-class majority glimpsed in the biggest struggles of the preceding years.

Of course, the ISO was far from the only organization to look to the lessons of the revolutionary socialist tradition. Indeed, there were many more such organizations then compared to today.

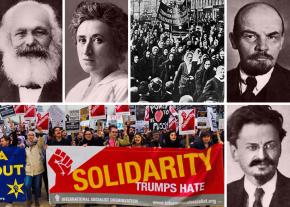

Then as now, the ISO attempted to distinguish its vision of socialism by starting from the bedrock definition put forward by Karl Marx when he wrote the rules for an international alliance of revolutionary organizations of his own day: "[T]he emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves."

Among the different ways of understanding and applying socialism and Marxism, the ISO stands in a tradition summarized by American socialist Hal Draper as "socialism from below." Contrasting this conception to socialists who looked to countries where a minority ruled in the name of socialism, or others who believed socialism could be elected into power or achieved little by little within capitalism, Draper wrote:

The heart of Socialism-from-Below is its view that socialism can be realized only through the self-emancipation of activized masses in motion, reaching out for freedom with their own hands, mobilized "from below" in a struggle to take charge of their own destiny, as actors (not merely subjects) on the stage of history.

Draper's phrase "socialism from below" was meant to distill not only the contributions of the towering figures of the tradition, like Marx himself, but also the experiences of the working-class movement over decades and centuries.

This article will try to trace some of those contributions and experiences to give an overview--and far from a comprehensive one--of where the ISO comes from.

The ISO began as a very small organization, and while it has grown, it is still small compared to its aims. If we have had success, it is because we stand on the shoulders of many giants at once.

But the same has been true throughout the socialist movement. Marx and the other revolutionaries we look to in history would be the first to say that their ideas and achievements were impossible without the many struggles of workers, students, intellectuals, and the poor and oppressed that inspired and shaped them--and without the dense web of radicals and revolutionaries connected to those struggles who tried to advance them.

WHAT ARE the basic elements of the ISO's vision of "socialism from below"?

The first is a clear understanding of what the working class needs to emancipate itself from: capitalism.

There has never, in the history of the socialist movement, been any shortage of atrocities and horrors to galvanize our desire to change the world--war and violence, dictatorship and repression, poverty and low wages, racism and oppression. But Marx and those who followed him share an understanding that all these individual crimes are connected to, and driven by, the capitalist system.

Socialists struggle against all the many injustices of today's world, but we also trace each back to their source in a social structure that allows a minority ruling class to amass wealth and power, while the vast majority in society are excluded from both.

This understanding has been critical from the beginning of the Marxist tradition, with Marx's writing that showed how capitalism is based on a hidden-in-plain-sight theft--that the capitalists, because they own, are able to make profits by exploiting those who own nothing, and have nothing to sell but their ability to work.

Marx extended this analysis of the relationship between exploiter and exploited to show how it took on particular forms, also involving specific kinds of oppression. One of the most powerful sections of his masterwork Capital describes how the kidnapping of Africans to work as slaves in the Americas was the basis on which capitalism could rise to new heights.

This view of capitalism as the source of not only exploitation but a multitude of oppressions adds another dimension to the bedrock definition of socialism: The emancipation of the working classes has to be accomplished by the whole working class, united in struggle--because unless divisions among workers are challenged and overcome, socialism can never succeed.

This is why, in the ISO's view, socialists must be a "tribune of the people...able to react to every manifestation of tyranny and oppression," in the words of the Russian revolutionary Lenin. For us, socialism must include the liberation of African Americans and other victims of racism, the emancipation of women, the liberation of LTBTQ people and all others subject to different forms of oppression--or it isn't socialism.

EVEN IN his most technical writings describing the workings of capitalism and the social structure and institutions built upon it, another theme runs through Marx: that poverty and oppression produce resistance. He and his collaborator Frederick Engels spelled this out in the opening of the Communist Manifesto: "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles."

Marx and Engels developed their particular vision of socialism in contrast to the prevailing ideas of other early socialists, such as the utopians, who saw their job as critiquing the existing system and coming up with plans for an alternative that would be accepted by universal acclaim because it was so much more rational.

Marx and Engels reacted against the paternalism of the utopian socialists. They had a different way of thinking about socialism: It wasn't about anticipating the new society or debating its shape in advance, but finding the new world in what existed in the old--and in particular, what existed in the struggles of the old.

"Self-emancipation" for them wasn't just a preference--what they would pick given a choice between different roads to socialism. For Marx and Engels, workers' power was at the same time the only possible path to socialism and its only real meaning.

This is why Marx and Engels were not only theoreticians and journalists, but activists and organizers. They were part of the democratic political struggles against the old order of kings and aristocrats that reigned in most of Europe at the time. They believed that victories for political democracy could advance the struggle for economic and social goals.

The ISO follows this same method: As socialists, we don't stand on the sidelines, but participate in all the struggles in society that we can, putting forward our analysis as a contribution to the fight in the here and now. But we also see these struggles as training grounds--both for the working class and for socialists among them--for the fight for socialism.

Marx and Engels summarized this organizational method in the Manifesto:

The Communists fight for the attainment of the immediate aims, for the enforcement of the momentary interests of the working class; but in the movement of the present, they also represent and take care of the future of that movement.

Because of their participation in and observation of practical political events and struggles, Marx and Engels came to the conclusion not only that socialism couldn't be dreamed into existence, but that a social force--with sufficient economic and political power to counter the rulers of society--was needed: the working class.

They recognized that, unlike other exploited classes, workers were forced by the conditions of work under capitalism to cooperate--which lays the basis for cooperation in resistance, and ultimately for political and social cooperation.

Of course, at almost all times under capitalism, this power of a united working class movement only exists as a potential. But it was essential to the socialism of Marx and Engels that the class struggle could stimulate this potential of the workers united to exercise their collective power.

Marxism's insistence on the centrality of the working class remains at the heart of the ISO's understanding of socialism. We have always resisted trends on the left, including among people who stand in the Marxist tradition, to identify another social force that could achieve socialism.

IN THEIR own time, Marx and Engels started out as a minority among other socialists who believed a new society would be accomplished by individuals or small groups of dedicated revolutionaries acting on behalf of the majority--either by putting forward the example of a utopia or through some political conspiracy.

After Marx's death in 1883, another version of this "socialism from above" came to dominate the international movement, over the objections of Engels and others.

In particular, the Social Democratic Party in Germany, with the largest mass membership of any socialist party, was guided by a doctrine known as "reformism": The idea that socialism would become possible within the existing system as working class parties won greater political power through elections and achieved a succession of reforms that transformed capitalism.

Rosa Luxemburg was the central figure to challenge this revising of Marxism's revolutionary core. In Reform or Revolution and other writings, she championed the mass struggles of workers and insisted that these couldn't be sidelined by a focus on elections. She wrote:

People who pronounce themselves in favor of the method of legislative reform in place of, and in contradistinction to, the conquest of political power and social revolution do not really choose a more tranquil, calmer and slower road to the same goal, but a different goal. Instead of taking a stand for the establishment of a new society, they take a stand for surface modifications of the old society.

The echoes of Luxemburg's argument reverberate for the ISO to this day.

We don't support either of the two mainstream parties in the U.S. political system because both are dominated by capital--the Democrats included. But even if the Democrats were a reformist party, we don't believe that elections are they way to achieve socialism. Elections under the existing system are a means to advance socialist ideas and working-class demands, but they aren't the only means by a long shot.

In the international debates about the meaning of socialism and the application of Marxism, one of Luxemburg's allies on the "revolution" side was the Russian socialist Lenin.

He added to her case against reducing socialism to winning political power under the existing system. Drawing on Marx's writings about the Paris Commune, Lenin showed in State and Revolution how the elected bodies of government had only partial power over the capitalist state--and practically no powers in a capitalist economy ruled by private ownership.

However, Lenin's best-known contribution to the Marxist tradition--both theoretical and practical--was on the question of how socialists should organize.

Rather than the prevailing view that socialist parties should aspire to encompass the whole working class, Lenin sought to build organization that drew together the most advanced workers--those more convinced, either intellectually or through their own experience, of revolutionary politics.

Such a "vanguard party" would be capable of the kind of internal democracy needed to give all members a real say in the direction of the organization--and of the centralism needed for a socialist organization to be effective in the class struggle.

Lenin's vindication was the decisive role of his party in Russia during the revolution of 1917. The Bolsheviks were key to the opening act of the revolution that toppled the hated Tsar, but even more so to final act: the establishment of a workers' state, based on the democratic rule of the majority. The Bolsheviks succeeded in this because they rose to the challenge of winning influence and support among the mass of rebelling workers and soldiers.

NONE OF these basic components of international socialism as the ISO understands it can be separated from the struggles of workers and the oppressed throughout history.

The practical experience of participation in struggle was indispensible for Marx and all the Marxists after him in developing their political and theoretical generalizations. And those generalizations in turn guided socialists in their activities and initiatives in real-world events.

The struggles themselves--especially revolutions, where class struggle reaches its highest peak and sometimes breaks through by toppling the old order--are a vindication of that bedrock definition of socialism: the self-emancipation of the working class.

Thus, the 1917 Russian Revolution is inspirational not only for the many revolutionary proclamations and policies put in place in the time that it survived, but in the way that the whole of Russian society came alive, mobilized to play a part in the making of a new world in ways that are impossible to imagine under capitalism.

There have been other revolutions and revolutionary upsurges since 1917, though none that succeeded in establishing workers' rule for more than a very short time. But all of them--the wave of revolutions in Germany from 1918 to 1923, Spain's upsurges of the 1930s, the Hungarian revolution in 1956, Portugal in 1974, Iran and Poland half a decade later--share the common features of mass participation and the flowering of democracy.

This is at the core of socialism for the ISO. Leon Trotsky elaborated on the concrete meaning of "self-emancipation" in his History of the Russian Revolution:

The most indubitable feature of a revolution is the direct interference of the masses in historical events...The history of a revolution is for us first of all a history of the forcible entrance of the masses into the realm of rulership over their own destiny.

TRAGICALLY, THE Russian Revolution did not survive for many years.

The first lasting experiment in workers' power was besieged by the military forces of foreign governments, which supported the counterrevolutionary remnants of the Tsar's regime. Russia was decimated by civil war and famine. The working class that made the revolution was reduced to a fraction of its former size and power. A workers' state couldn't survive in Russia with the working class physically destroyed.

The Russian revolutionaries always understood that maintaining socialism in a single country would be impossible if the revolution didn't spread. Though the workers of Hungary, Germany and Finland came tantalizingly close to making their own revolutions, Russia ultimately remained alone, setting the stage for counterrevolution.

But the form of this counterrevolution took wasn't the triumph of the Tsarist reaction or conquest by a foreign army. The workers' state survived the civil war militarily. But a section of the state bureaucracy, coalescing around Joseph Stalin in the years after Lenin's death, seized the powers of a minority ruling class and began wielding them--while all the while claiming to be socialist.

One decade after the revolution, the Stalinist rulers of Russia had begun to reverse all the gains of the 1917 revolution, while imposing iron control--politically, economically and socially--over society, all the while using the language of socialism and Marxism.

This specific form of the defeat of workers' power in Russia enormously complicated the question of what is socialism for future generations.

Even as Russia's rulers acted more and more as the polar opposites of socialists, the vast majority of revolutionaries around the world remained committed to the belief that Russia was a socialist society--understandably enough, given the prestige of the first successful workers' revolution, which, of course, the Stalinists used to their advantage.

Leon Trotsky led an opposition within Russia to maintain the socialist and internationalist principles of the 1917 revolution, but he and his supporters couldn't overcome the growing strength of the Stalinists.

Against the backdrop of tyranny and oppression restored in Russia, the victory of fascism elsewhere in Europe and the drive to another horrific world war, adherents to the Marxism of Marx, Luxemburg and Lenin were driven to the smallest of margins.

That a tradition committed to working-class self-emancipation survived at all was the result of the heroic efforts of Trotsky and his small group of followers. Though he was one of the two best-known leaders of the 1917 revolution, Trotsky nevertheless believed that his most important contribution came during these dark days in keeping alive genuine Marxist ideas and organization.

If you believe that Russia under Stalin--or any of the other countries later modeled on the USSR in one way or another--was a socialist society, then there is a greater tendency to be pulled toward a conception of "socialism from above," with implications that are not only theoretical, but practical in the struggles of today.

THIS QUESTION of what is socialism dominated further differences that crystallized within Trotskyism, despite the common opposition to Stalinism.

After the horrors of the Second World War--and the murder of Trotsky by a Stalinist agent in 1940--Stalin's Russia was able to establish an empire of satellite regimes across a third of Europe.

Many Trotskyists stayed loyal to Trotsky's conception that Russia, though ruled by Stalin's counterrevolution, still retained elements of a workers' state, like nationalized property, and so it was to be defended against the private capitalist empires of the West. But what to make of these new "workers' states" that were the mirror image of Russia in every way, but which had been established by military conquest, not the self-emancipation of the working class?

Others among the Trotskyists sought to preserve the centrality of Marx's definition. There were different understandings of exactly what did exist in the USSR, but these revolutionaries began to conclude that neither Russia nor the regimes modeled on it could be considered workers' states in the sense used by Trotsky.

Among a grouping of individuals and organizations internationally, a common slogan emerged: Neither Washington nor Moscow but International Socialism. The current within Trotskyism that took the name International Socialism is the immediate source of the ISO's political and organizational inheritance.

There were a number of figures and groups associated with this tradition. In the U.S., Max Shachtman, a founder of Trotskyism in America in the 1920s, and Hal Draper were leaders in a succession of organizations and formations. In Britain, Tony Cliff, an exiled Jewish revolutionary from Palestine, was at the center of founding the International Socialists, later re-established as the Socialist Workers Party-UK.

These groups and groupings distinguished themselves in their analysis of Russia and their understanding of Marxism. But they were also wholly committed to the struggles of the day, their practical activity guided by a vision of "socialism from below."

In the U.S., socialists of the IS tradition played an unheralded role building support in the North for the civil rights movement. During the 1960s, the Independent Socialist Club was formed literally in the midst of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement by leaders of that struggle, which served as a launching pad for the anti-Vietnam War movement.

The struggles of the 1960s and early 1970s reignited mass interest in revolutionary politics, far beyond anything contained to the IS tradition. Many more revolutionary organizations were revived or formed, and thrived through their commitment to fighting against war and for liberation.

The now-renamed International Socialists in the U.S. was not the largest of these, but it was part of the major struggles of the era, particularly around labor. With hundreds of members by the mid-1970s, its contribution to the renaissance of Marxist theory and organization is distinctive. In Britain, the IS and later SWP-UK grew even larger on the strength of a radicalization that was more directly driven by working class struggle than in the U.S.

The ISO was founded in 1977 by members of the IS who had been expelled after a debate largely over the analysis of the political situation and of what tasks socialists should set for themselves. This is frequently the most difficult and contentious of questions for socialists to answer: How to apply socialist and Marxist analysis to figure out what is to be done next.

But the dedication to the history and tradition of socialism from below prevailed more widely then, as it does today.

Forty years later, we define ourselves by that tradition, and our tasks remain the same: To use every opportunity to build struggles and organization in order to advance the working class movement in the here and now and to prepare for the future when we can fight for a socialist society.

We hope you'll join us in that project--there's a world to win.