The foxes tear down a flimsy henhouse fence

The Trump administration is going after the Dodd-Frank financial reforms, proving that Wall Street will try to overturn even inadequate regulation, writes .

ON FEBRUARY 3, Donald Trump issued an executive order setting out his administration's "Core Principles for Regulating the United States Financial System," which instructed the Treasury Department to identify any laws, regulations or government policies inconsistent with these "core principles."

The order may express them in vague bureaucratic terms, but Trump's many public pronouncements prove beyond any doubt that the new administration's main principle is serving unrestrained corporate greed.

Although it's never named in the order, a primary target of Trump's directive is the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, the massive and complex bundle of measures enacted by the Obama administration in response to the financial crisis of 2007-08.

To win votes last year, Trump promised to "drain the swamp" in Washington. But his administration is filling up with the same banksters who caused the financial crisis. Trump is drawing alumni from the same mega-bank, Goldman Sachs, that prevailed during the Bush administration, with six top executives--including Gary Cohn, the former president and second-in-command at Goldman--helping to "make America greed again."

Is it any surprise that the administration is unraveling the new Dodd-Frank rules they loudly opposed as "private" citizens?

DEMOCRATS MAINTAIN that Dodd-Frank has restrained or done away with many of the worst abuses of the financial system. But the act always fell far short of what was needed.

It's important to remember that in 2009-10, when Dodd-Frank was introduced, debated passed by Congress and signed into law, the Democrats held the White House and majorities in both the Senate and House. They had essentially a free hand to create whatever legislation they wanted, without needing to seek compromises with Republicans.

What they did create, as SocialistWorker.org noted at the time, was "a hodge-podge of half-measures that will do little to alter Wall Street's business practices, much less prevent another major crisis...At most, [Dodd-Frank] increases the power of some regulators to constrain--or not constrain--Wall Street's behavior."

The Democrats thus revealed themselves to be more concerned with preserving the existing financial system, with a few minimal adjustments as a nod to "reform," than with overhauling it in any meaningful way.

Nonetheless, from a capitalist point of view, "no regulation" is preferable to "weak regulation"--and so Republicans in Congress are only too eager to help Trump tear down Dodd-Frank.

In fact, the assault has already scored its first victory.

On February 14, Trump signed legislation repealing recently enacted rules implementing Dodd-Frank's requirement that publicly traded fossil fuel and mining companies disclose payments to foreign governments.

Trump justified the law with his usual bravado. "We're bringing back jobs big league," he told the press. "We're bringing them back at the plant level. We're bringing them back at the mine level. The energy jobs are coming back."

In reality, this repeal is a gift not to workers, but to executives in the energy industry, who have been lobbying against the measure in Dodd-Frank since the day it was proposed.

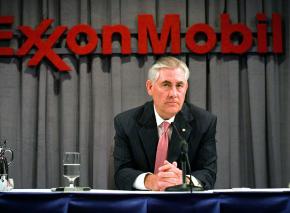

Among the most vocal opponents was none other than current Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. In 2010, he was the CEO of ExxonMobil--and he "and one of his lobbyists paid a half-hour visit to the amendment's Republican co-author, then-Senator Richard Lugar, to try to get it killed," Politico reported recently.

Tillerson failed to get the measure removed, but he and his allies did manage to keep the regulations needed to implement it from being put in place until June of last year. Because of the long delay, Republicans were able to repeal the regulations quickly this year, under the terms of the Congressional Review Act, which grants Congress a limited time frame to strike down new regulations by a simple majority vote.

MOST OF the major components of Dodd-Frank have been in place for years, however, so a more robust legislative effort will be needed to overturn them. To this end, Republicans have reintroduced the Financial CHOICE Act, first proposed last year.

This bill takes aim at many key elements of Dodd-Frank, including: the Durbin Amendment, which limits fees charged to retailers for debit-card processing; the Volcker Rule, which restricts banks from gambling on risky investments for their own profit; and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), a new agency tasked with protecting consumers from abuses by the financial sector.

In fact, each of these examples reveals different deficiencies in the design and implementation of Dodd-Frank.

For instance, the Durbin Amendment, named for its sponsor, Illinois Democratic Sen. Richard Durbin, placed limits on debit-card processing fees, but did nothing to limit credit card processing fees--a clear gift to the banking industry. The amendment also did nothing to stop banks from imposing additional charges on consumer accounts to make up for "lost" fees--which, predictably, many banks did.

The Volcker Rule, meanwhile, began life in a three-page letter from former Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker to President Obama; grew to 10 pages by the time it was added to Dodd-Frank; and was ultimately implemented via regulations running to just under 300 pages.

Thanks to years of lobbying and legal wrangling, the rule is so choked with exemptions and loopholes that--having won as many concessions for themselves as possible--Wall Street could then turn around and declare the finished product to be impossibly complex, and call for its repeal.

As for the CFPB, Dodd-Frank limited the scope and effectiveness of its activities by explicitly capping the bureau's annual budget--uniquely among bank regulators--and imposing substantial burdens, some of them also unique, on its rulemaking process. The CFPB's regulations can also be blocked by the interagency Financial Services Oversight Council, if that body decides they are a threat to financial stability.

Perhaps the most damning indictment of Dodd-Frank--certainly the most obvious one--is that despite its stated objective of "ending 'too big to fail' banks and other institutions," the U.S. financial system continues to be dominated by a small number of immense, interconnected and politically influential institutions, whose failure is unthinkable for U.S. political leaders.

Obviously, none of this makes the current administration's assault on Dodd-Frank a cause for celebration. Rather, it serves as a reminder of the limitations to achieving meaningful reform via the political process, no matter which party nominally holds power.

Dodd-Frank's "reforms" were always deeply flawed and inadequate. But now that Trump is poised to tear down even these meager checks on Wall Street greed, the need for a mass movement demanding genuine change is greater than ever.