Who gets the bird: the hunter or the dog?

The 1930s upsurge of union organizing demonstrates the need for radicals to use a bottom-up strategy, explains , in an article first published at Jacobin.

IN SEPTEMBER 1936, a group of 10 affiliated unions calling itself the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO) was ejected from the American Federation of Labor (AFL) by vote of the executive council. Led by John L. Lewis and the United Mine Workers, the CIO would go on to become the most powerful labor organization in U.S. history, attaining a level of national clout never matched before or since its heyday.

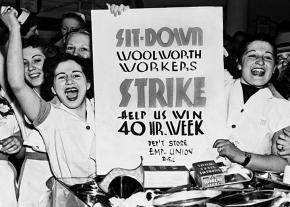

During the 1930s, the CIO rolled through the industrial heartland of the United States like a juggernaut, inspiring millions of workers to wage thousands of strikes and organize themselves into permanent local unions. CIO-affiliated militants, spread across the bastions of basic industry, worked together to build a system of industrial pattern bargaining that set wages and working conditions for millions of U.S. workers (even beyond the ranks of the labor movement) and could be called upon to shut down entire sectors of American capitalism.

Though its role is rarely mentioned, and even less frequently assessed, the left was central to the organization of this new dissident union federation. Thousands of socialist activists participated in the small and large battles that built the CIO over the two decades of its existence, and their victories and mistakes profoundly shaped the union federation's history.

Though 80 years have passed since the heroic years of the early CIO, the period still offers plenty of lessons for socialists and union activists today.

The Lay of the Left

The radical left's long-running effort to build a presence in unorganized industries greatly aided the CIO's early organizing. Many of the cities where the CIO would grow to significant strength were areas where radical forces had been operating for decades through various organizations.

For example, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) had built a significant presence in the auto, rubber and steel industries in years prior. Other radicals had joined the Communist Party–supported Trade Union Education League (TUEL) in previous years, then drifted away when it was decommissioned. Members of the American Workers Party (AWP) had led the Toledo Auto-Lite strike and were members of the "federal" locals (directly affiliated to the AFL) in the auto industry.

The Socialist Party (SP) also had key areas of local strength--notably in the auto industry in Flint, Michigan, where it would go on to play a leading role in the 1936 sit-down strike. The SP also organized and maintained its own unemployed councils and had significant strength in the teachers' and machinists' unions, the garment industry and in some old-line building trades locals.

But the Socialist Party (SP) was also wracked by internal turmoil.

The SP had declined to a fraction of its former size since the early 1920s, when the leadership expelled roughly two-thirds of the party's membership in an attempt to maintain control of the organization.

With Roosevelt's administration in power, key sections of the Socialist Party would desert the organization to join the New Deal coalition, including the leaders of the garment unions--David Dubinsky and Sidney Hillman.

But even after the defections, the party still had roughly 7,000 dues-paying members and counted approximately 1,300 members spread out across 80 or 90 different unions, predominantly old-line AFL unions.

By 1936, American Trotskyists were concentrated in the Workers Party of the United States (WP), having recently formed the organization by fusing the Trotskyist Communist League of America with the AWP.

Both groups had played crucial roles in two of the three big strikes of 1934: the Trotskyist Communist League was instrumental in the Minneapolis Teamster strikes, and the AWP had an important presence in Toledo among the auto workers. So when the two groups came together in December 1934, they each had areas of local strength in the labor movement.

But by 1936 the WP had lost this momentum by embarking on a nearly two-year-long stratagem to enter the Socialist Party with the aim of capturing its radicalizing youth wing. In 1938, the remaining Trotskyists and AWP members would withdraw from the SP to again form their own organization--the Socialist Workers Party--but they were largely absent from the crucial first years of the CIO.

Communists on the Front Lines

Of all the left forces in the United States, the Communist Party would prove to be in the best position to make an impact on the new CIO. Since the late 1920s, the Communist Party had embarked on a strategy of building up new "red" unions in its own union federation, called the Trade Union Unity League (TUUL), in opposition to the AFL.

Although this strategy was an utter failure and provided the AFL's labor bureaucracy plenty of ammunition to use against the left--labeling left-wing organizers as "splitters" and "dual unionists"--CP cadres had gained years' worth of organizing experience in hundreds of hard-fought strikes, demonstrations and organizing campaigns.

By 1933 and 1934, the TUUL had more or less collapsed, as CP cadres abandoned the project of constructing "red" unions and instead participated in new federal locals or the reviving AFL unions. The CP helped lead the San Francisco longshoremen's strike of 1934 by working within the International Longshoremen's Association, an AFL affiliate. And by 1935, with the switch from the sectarian "Third Period" strategy into the new Popular Front policy demanded by Moscow, the CP would officially go back to their strategy of working within the AFL.

But the CP hadn't just chanced upon bases of support in key industries. An intentional strategy had been put into place in years prior. Randi Storch, a historian of the Communist Party in Chicago, explains:

To make up for their limited resources in Chicago and throughout the country, national Communist leaders pushed their trade unionists to develop a policy of "concentration"--a focused drive to recruit members in "the most decisive industries." Nationally, these included mine, steel, textile, marine and auto. Once they selected particular factories for concentration, Communists were supposed to hold gate meetings, pass out literature, provide aid to striking workers and develop a group of supportive union activists...In the face of a strike, the party was to offer legal assistance through the ILD [International Labor Defense, the legal aid wing of the CP] and strategic help through its leading trade unionists.

In Chicago, the CP focused its efforts on several industries--notably the packinghouse workers on the South Side. In New York City, the party would provide the initial organizing committee of the Transport Workers Union through one of its "concentration units" in the city's subway system.

Members of the local party organization weren't necessarily expected to drop their lives and to take jobs in a specified workplace, but they did help develop a local expertise on the issues and conditions in specific workplaces, help distribute literature and leverage their existing political relationships to recruit employed workers. Reports of shop conditions would be published in the Daily Worker, and used to connect with workers in the shops.

In Detroit, the CP had been building up strength in auto plants across the city since 1927, with 350 party members working in 12 shop units. In Milwaukee, a CP unit worked for years to unionize the massive Allis-Chalmers works--first by taking over a company union and making forceful demands on the company, then by forming AFL craft unions, then amalgamating them together into a factory-wide Federal Labor Union (FLU), and finally winning affiliation with the new United Auto Workers (UAW). In St. Louis, a CP concentration unit in the unorganized electrical appliance manufacturer shops would lead to the creation of District 8 of the United Electrical Workers. A similar pattern prevailed in many of the newly created unions.

As historians Judith Stepan-Norris and Maurice Zeitlin write of the CP's strength in the labor movement:

In 1934, a year before the dissolution of the TUUL and the party's decision to have it return to the AFL, a confidential CP memorandum reported that Communists were in the leadership of 135 AFL locals with a combined membership of over 50,000 as well as of "several" entire union districts; the memo said they also led organized opposition groups in another 500 locals. In 1935, with the TUUL's formal dissolution, these Communist bases in 635 AFL locals and entire districts were reinforced and new ones were established when Red union remnants rejoined the AFL, as intact units if they could be or, otherwise, as individuals.

The Communist Party's patient work building a base among rank-and-file workers had paid off, contributing to the development of a fighting labor movement and growing the CP at the same time.

The Hunter and the Dog

But the Communist Party also supplied an army of members to the CIO as paid staff, on the employee rolls of the new unions and chartered organizing committees. Top CIO leaders met early on with high-ranking leaders of the Communist Party and came to an agreement to employ hundreds of CP cadres as paid organizers for the new federation. Not to be outdone by their Communist rivals, the Socialist Party also worked to supply the CIO with their own members for paid staff positions in the UAW, the Textile Workers Organizing Committee and elsewhere.

The CP's chairman, William Z. Foster, estimated that in the drive to organize the steel industry, at least 60 of the 200 full-time paid staff were CP activists. Hundreds of other CP activists would go onto the CIO's payroll to contribute to organizing projects across the United States, maintaining an uneasy truce with top CIO leaders.

As valuable an opportunity as it was, an emphasis on permeating the ranks of labor staff positions and officialdom was fraught with political difficulties and imposed limitations. When questioned about his hiring of Communists onto CIO payrolls, John L. Lewis famously retorted: "Who gets the bird? The hunter or the dog?"

The truce held for several years, but with CIO leaders firmly in control of the machinery of the new federation, the "dog" was never given too long of a leash. Whenever more moderate CIO leaders thought CP organizers went too far or were too public with their views, they were quietly fired. Whenever CP organizers were successful in chartering new locals, they were immediately directed away to work on new campaigns, undercutting organizers' ability to develop bases of support for left-wing politics.

Lewis and his successor Philip Murray knew that despite the CP's organizing experience and influence as union staff, the top CIO leaders were ultimately the people calling the shots. Once political alignments within the CIO shifted, the truce would be over.

When the truce ended in the years following World War II, the fratricidal struggle that broke out within the CIO was brutal. The Communist Party endorsed Henry Wallace's campaign for president on the Progressive Party ticket in 1948, going against the top CIO leadership, which had backed Harry Truman as the Democratic nominee despite Truman's deep unpopularity within the labor movement. While much broader forces were at work driving a wedge between the Communist Party and the top CIO leadership, this perceived act of disloyalty was the immediate catalyst that provoked a wholesale purge of left-wing CIO organizers.

Philip Murray purged the entirety of the CIO national staff. Left-wingers in staff positions found themselves uniquely vulnerable to redbaiting, and were easily removed from the payrolls. Others were given the choice of resigning their party membership or quitting their jobs, and some chose to quit the party.

To make matters worse, when contested union elections ousted Communists from union office, hundreds of CP organizers, researchers, and educational and regional directors were promptly fired, proving how fragile their palace influence could actually be.

In the Transport Workers Union--where the CP had developed only a small shop-floor following, but was disproportionately represented among the staff--the party's presence was virtually wiped out when Mike Quill, president of the TWU and for years a CP "notable," turned on his erstwhile comrades and purged the entire union payroll.

Eventually Murray would expel 11 left-led unions from the CIO in 1948--ejecting something like a quarter of the CIO's total membership--and then charter entirely new rival unions to raid and destroy them, like the International Union of Electrical and Radio Workers, which nearly destroyed the UE.

But when the Communist Party possessed a strong base on the shop floor in serious numbers within specific unions, they proved far more difficult to dislodge. For years the left-led unions actually held their own, and only acquiesced to join the merged AFL-CIO after McCarthyism, ugly CP internal battles, increased raiding, and the loss of legal certification under the Taft-Hartley Act.

Towards the Shop Floor

Any revival of a left-wing unionism today will have to involve a serious emphasis on building a shop-floor presence within unionized workplaces, rather than just in the union staff positions more attainable for the political left. With an entrenched leadership bureaucracy committed to a failed strategy of collaboration with U.S. capitalism, union staff will always be limited in their role.

While individuals can do great work and contribute real talent, the task of reforming and reorganizing the U.S. labor movement remains a political battle to be won within the unions through a rank-and-file upsurge from below. Many of today's union leaders recognize this--and, like John L. Lewis, they'll knowingly deploy left-wing organizing staff despite being unfriendly to left-wing objectives, because they're entirely confident that the union, and not the leftist political project, will end up keeping "the bird."

Despite the Communist Party's enormous shortcomings--including the opportunism of the Popular Front era and their shameful role during World War II--many CP-led unions nonetheless left an inspiring legacy. Many locals waged militant strikes and aggressively expanded the "frontier of control" on the shop floor far beyond the legal interpretations of collective bargaining.

Some local unions even fought against employer racism on the shop floor, working to integrate lily-white occupations and sponsoring national campaigns against Jim Crow. Others fought for equal pay for women, or argued for "super seniority" to benefit Black workers threatened with layoffs because they were typically the last hired and first to be fired.

The extent to which CP members built bases of rank-and-file support in the young CIO unions gave them a persistent presence which took years to root out. It would only be through the open collusion of the top CIO leadership, employers, local and national media, and the federal government that Communist Party influence on the shop floor would finally be destroyed in the 1950s, during the darkest days of McCarthyism.

Socialists within the labor movement must adopt a strategy of building up bases of local support that can be leveraged within and between unions for coordinated aims. Socialist politics are crucial to building a fighting labor movement, capable of giving expression to worker militancy across various industrial sectors and, ultimately, even the entire economy.

But for a socialist project to have long-term standing and weight among organized workers, years of patient organizing are required.

First published at Jacobin.